Special Counsel Robert Mueller has left little doubt in detailed court filings that Russians interfered in the 2016 presidential election and tried to help Donald Trump defeat Hillary Clinton.

His soon-to-be-released report may answer the most pressing remaining question: Did Americans in Trump’s orbit conspire with any of those Russian efforts?

During Mueller’s two-year investigation, Americans have learned that Trump’s associates repeatedly interacted with Russians and their conduits. Now, the special counsel could connect any dots — if they exist — and determine if the campaign worked with Russia to get Trump elected.

As for Trump’s culpability, Mueller may find it difficult to render a judgment, a task complicated by the president’s leadership style — his avoidance of emails and texts, his aversion to direct orders, his deviations from the truth. Mueller is also examining whether the president’s actions and words constitute efforts to obstruct justice.

Attorney General William Barr will make public a summary of the sealed report after he gets it. Justice Department policy prohibits indicting a sitting president and restricts releasing material on people not charged, meaning details about Trump’s inner circle could be scant.

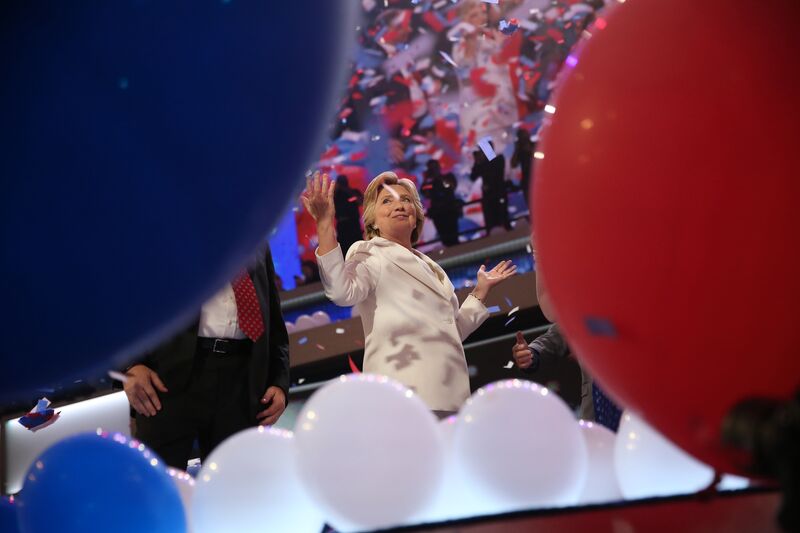

Prime Beneficiary

As for the Russian efforts themselves, Mueller has already narrated, in criminal cases rolled out over more than a year, how he says Moscow set out to influence the presidential election. Their prime beneficiary, in Mueller’s telling, was Trump, a businessman who had pursued deals in Moscow for two decades.

Mueller’s filings lay out an audacious plan that began in 2014 when a so-called troll farm based in St. Petersburg, the Internet Research Agency, developed an information warfare strategy to sow political discord in the U.S.

Taking to Facebook, Twitter, YouTube and Instagram, the Russians used phony online identities to tear down Clinton and other Trump rivals, while repeatedly touting Trump. They pumped out slick content for hundreds of thousands of followers on topics including Black Lives Matter and Muslims. They arranged grassroots rallies. A Russian troll, impersonating an American, asked someone in the U.S. to build a cage on a flatbed truck, while hiring someone else to wear a costume depicting Clinton in a prison uniform.

Thirteen Russians were indicted. They haven’t responded to the charges. The indictment was careful to note that Russians took advantage of Americans, including some associated with Trump’s campaign, who were unwitting.

By 2016, Russia’s military intelligence agency, known as the GRU, started a complementary effort. It set out to hack emails and documents from the Clinton campaign, its chairman John Podesta, and the Democratic National Committee. The indictment of a dozen Russians, who haven’t responded in court, was peppered with rich details of where the alleged hackers worked and how they funded their efforts.

The GRU began releasing thousands of emails in mid-2016, using websites and social media accounts with fake personas, according to the prosecutors. Some stolen documents, including from Podesta, were transferred to WikiLeaks, the anti-secrecy organization founded by Julian Assange. It released emails at strategic times — including just before the Democratic National Convention and just after the Washington Post released a 2005 audiotape of candidate Trump boasting about sexually assaulting women.

Information Hunt

At roughly the same time, Trump associates were getting wind of just the sort of information the Russians were dredging up. Some in the candidate’s circle sought damaging information on Clinton, including hacked emails. The open question, at the core of Mueller’s mission, is whether there were any “links and/or coordination” between the Russian government and individuals associated with Trump’s campaign.

That June, Donald Trump Jr. attended a meeting at Trump Tower with several Russians based on a promise of “dirt’’ on Clinton. Russian lawyer Natalia Veselnitskaya and lobbyist Rinat Akhmetshin were there, as was Trump’s son-in-law Jared Kushner and his campaign chairman, Paul Manafort. Conflicting versions of the nature of the meeting emerged. Mueller is trying to determine if it amounted to collusion.

Trump himself famously looked into the camera with a plea for emails from Clinton’s private server. “Russia, if you’re listening, I hope you’re able to find the 30,000 emails that are missing,” he said on July 27, 2016. It was the very day, according to a Mueller indictment, that the Russian military intelligence squad made its first attempt to hack a domain used by Clinton’s personal office.

At the Crossroads

The figure who may be closest to the crossroads of the campaign and Russian hacking efforts is longtime political operative and Trump ally Roger Stone.

Mueller has laid out, in two indictments, Stone’s efforts to obtain emails and voter data hacked from the Democrats. In one instance, in August 2016, Stone reached out to an online persona called Guccifer 2.0, who purported to be a lone Romanian hacker, and sought the purloined emails. Instead, Guccifer — who Mueller said was an alias of the GRU officers — provided voter information hacked from the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee. In return, Stone later analyzed it for Guccifer.

That same month, Stone claimed publicly that he had communicated with Assange, who’s been holed up in the Ecuadorean Embassy in London since 2012 to avoid extradition to the U.S. An October surprise was coming, Stone added.

On Oct. 4, 2016, a senior campaign official asked Stone about future releases by WikiLeaks, and he replied that it would release “a load every week going forward.’’ Mueller has charged Stone with false statements, obstructing the congressional investigation, and witness tampering. He’s pleaded not guilty.

‘To the Heart’

Mueller has also homed in on a meeting that one prosecutor said goes “very much to the heart” of its investigation — an August 2016 meeting between Manafort, Trump’s then-campaign chairman, and a business associate named Konstantin Kilimnik who Mueller says has ties to Russian intelligence. During the meeting at an upscale Manhattan cigar bar, Manafort allegedly shared polling data and discussed a peace plan for Ukraine, where the pair had long done work for pro-Kremlin politicians. Details of the meeting came out after Manafort was convicted of fraud and other charges.

The connections with Russia continued after Trump’s election. Several people on his transition team held secret conversations with top Russian officials about U.S. foreign policy in the new Trump administration. They included Trump’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner, and Michael Flynn, who briefly served as national security adviser. Flynn pleaded guilty to lying to the FBI about those conversations and awaits sentencing. Kushner omitted some of the names from security clearance documents in error, a representative has said, and he later disclosed them.

He noted that Mueller contrasts with Kenneth Starr, the independent counsel who spent four years investigating President Bill Clinton two decades ago. Starr, he said, made “no secret’’ of his desire to fuel an impeachment of Clinton. Mueller’s mission is different, he said.

“Bob Mueller has been asked to go out and investigate a far broader and far more important matter,’’ Cotter said. “This is about our democracy and a foreign power.’’